by Matthew Raley Let's make that, "Lessons Camping has taught inadvertently."

1. An interpreter of the Bible has to exhibit sound reasoning.

Camping consistently appeals to what he calls the "spiritual" meaning of the text. There's what a passage says, and then there's a secret code in it that contains what God really meant. You crack the code by "comparing Scripture with Scripture," as Camping likes to say. This procedure of his reduces to cut-and-paste: pull this fragment of a verse from here, join it with this bit of numerology from there, and, lo, the "spiritual" meaning is clear.

There is no "spiritual" meaning of Scripture. There's just the meaning. "Spiritualizing" is nothing but an escape hatch for a teacher who can't find a legitimate connection between a biblical passage and life. And Camping is far from being the only pastor who uses it.

We grasp the meaning of the Bible in the usual way: by applying the knowledge of vocabulary, grammar, history, genre, literary allusions, and lines of reasoning. Many pastors do not want to do the work of learning these things, much less be held accountable for demonstrating that their interpretations are valid.

Which brings us to ...

2. Debate among pastors and scholars is a safeguard for congregations.

If you're going to teach God's word, you'd better be prepared to argue your case. Pastors are guilty of a breach of ethics when they refuse to answer questions, or debate the many problems of interpretation, or expose the line of reasoning behind their preaching. A pastor owes it to his people to be accountable to the community of scholars in this way.

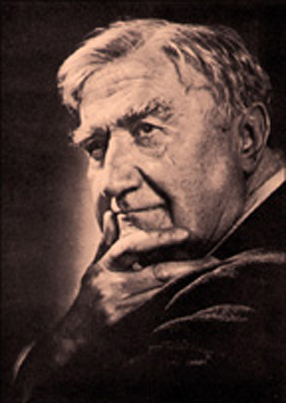

Camping is a classic prophet-leader, who relies on his authority over his followers to answer all questions.

Today, just as many pastors don't want to debate, so many believers don't want to hear arguments, regarding debate as inherently divisive. I hear people say, "Let's not argue about words. We all believe the same God."

Their aversion to public argument is foolish. It reduces every disagreement to a matter of preference between the personalities or styles of teachers, instead of recognizing that there are real issues to be decided that are larger than mere points of view. The folly of this reductionism is that a cult leader like Camping thrives in a contest of personal loyalty.

Where mere personal appeals are the issue, believers are not safe. They need to be challenged to think, not just prefer.

3. A Bible teacher is responsible for what he teaches.

Camping keeps saying, as many pastors say, "I'm just teaching the Bible. I'm not responsible for what it says."

This is another escape hatch. As a teacher, I am responsible for what I teach. I am not at liberty to equate my interpretations with the Bible, so that if you reject my teaching you are by definition rejecting God. I am morally accountable for my expositions of Scripture, for the workmanship of my sermons, for the clarity of my reasoning, and for the precision of my applications.

This is an awesome responsibility. A few people's hope, health, and decision-making are deeply influenced by what I say. This reality is what drives me to study: When I come before the throne of God, the Lord will render a verdict on whether I accurately taught his word.

Camping should repent of his self-indulgence. Judgment Day is indeed coming for him.