by Matthew Raley

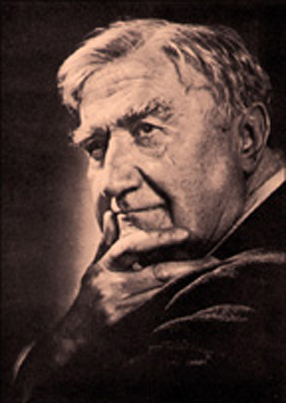

I've given several examples of Alfred Hitchcock's abstract visuals in Vertigo (here and here). But Hitchcock also created a sound-world to match, and he found a collaborator in Bernard Herrmann. Together, they raised the score to the level of co-narrator with the camera.

I've given several examples of Alfred Hitchcock's abstract visuals in Vertigo (here and here). But Hitchcock also created a sound-world to match, and he found a collaborator in Bernard Herrmann. Together, they raised the score to the level of co-narrator with the camera.

The term “Wagnerian” is often used to characterize Herrmann’s score for Vertigo, and for good reason. But the variety of composers who influenced Herrmann hints at a more complex musical imagination.

He was famous for loving English composers such as Edward Elgar[1] and Ralph Vaughan Williams.[2] Vertigo’s frequent similarity to music by Claude Debussy is mentioned by critics.[3] Less well-known is Herrmann’s study as a thirteen-year-old of Hector Berlioz’s Treatise on Orchestration. The influence this Romantic maverick had on Herrmann was life-long.[4] Nor was Berlioz the only musical outsider with whom Herrmann identified. Though Herrmann spent his student years in New York close to such American icons as Aaron Copland and George Gershwin, Herrmann also developed relationships with young radical composers in a group modeled on Les Six.

Most significantly, Steven Smith documents Herrmann’s long association with Charles Ives, the ultimate outsider, noting Herrmann’s early study of Ives’s 114 Songs and his habitual visits with Ives until Ives died in 1954.[5]

With such a background, there should be no surprise that Herrmann’s score is one of the more abstract elements of Vertigo.

It is not explicitly tonal—that is, the harmonies are not organized around a triad that specifies a key, but around the pitch-class structures and intervallic relationships that occur in the first bars of the prelude. Such harmonies, while not expressionistic, are at the outer reaches of the common practice era.

Herrmann, further, employs a modular phrase structure that permits the extension of a line, but is not intrinsically melodic, alluding to but not identical with the traditional eight- or sixteen-bar phrase.

As we will explore over the next posts, the abstraction of Vertigo’s music allows it to operate with subtlety, concision, and force. The score is a large part of the greatness of this film.

[1]Bernard Herrmann, “Elgar: A Constant Source of Joy,” in Edward Johnson, Bernard Herrmann: Hollywood’s Music-Dramatist, Bibliographical Series 6 (Rickmansworth: Triad Press, 1977), 29–31.

[2]Bernard Herrmann, “Vaughan Williams’s London Symphony,” The Musical Times 100, no. 1391 (1959): 24.

[3]William H. Rosar, “Bernard Herrmann: The Beethoven of Film Music?,” The Journal of Film Music 1, no. 2 (2003): 137; Royal S. Brown, “Herrmann, Hitchcock, and the Music of the Irrational,” Cinema Journal 21, no. 2 (April 1, 1982): 20.

[4]Steven C. Smith, A Heart at Fire’s Center: The Life and Music of Bernard Herrmann (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 14–15.

[5]Ibid., 21–23, 38–39.