What Makes a Relationship with God?

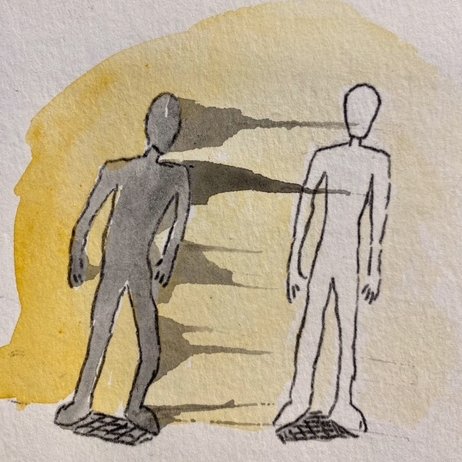

Illustration by Paul Mathers

Bear with me in a theoretical post.

Recently, I have been writing about classical theism, especially its impact on our emotional lives. God’s absolute independence (his aseity) is a source of vital strength for believers. Many say that God’s aseity destroys any idea that we can have a relationship with him. But in their effort to describe a two-way, give-and-take relationship with God, they blur God’s identity with ours. I am arguing that their concept of relationships does not exist at all.

Now I want to ask, “What constitutes a relationship? What causes it to be?” We are able to describe what constitutes other things. We might say, for example, that a human being is the union of body and soul. That union causes the human person to be. To take another example, we might say that a table is the assembly of a hard, flat surface on at least three legs. The assembly of those parts causes a table to be. What is the being of a relationship? We have said that a relationship is not the blurring of two identities. But what is it?

A relationship comes to be through communication.

A relationship is the history of messages given and received by two (or more) separate identities.

In my last post, I described an ex-husband who is so obsessed with his wife that he cannot accept their divorce. He tries to coerce her to stay in the marriage. Consider that relationship a little further.

His relationship with his ex-wife has a history, the record of their communication. He saw her the first time, he worked up the nerve to talk with her, told her that he loved her, asked her to marry him, etc. He also became angry with her, hit her, and called her names. She moved out, divorced him, and got custody of their children. That’s a lot of communication! The ex-husband would not be able to tell this history without also narrating his emotions about their relationship.

An alert observer might say, “That’s his history. What about hers?”

Well, her account would be very different. We would learn many things about the history of their communication once we gained her perspective. We might learn more things that he said and did—communication that he omitted. Maybe she would say that she was afraid of him from the first moment they met. Or we might learn that she was deeply in love with him and remains so even after their divorce. Like her ex-husband, she would only be able to recount their history by narrating her feelings.

The alert observer might then say, “Wait! There are even more histories of this relationship. His friends all have their histories of how the marriage grew and died. So do her friends. Their children have their own histories too.”

When we inquire this way, we realize that a relationship can be observed from both inside and outside.

Arguments will break out over the claims of each point of view, and those arguments would hinge on questions of fact. Did the husband hit his wife one night, or did he act like he was about to hit her? Did she tell her friend that she loved her ex-husband, or that she was afraid of him, or both?

A relationship is an event—a series of actions—observed from multiple points of view. The event occurs between people who have their own separate identities—occurs outside of them. Even so, the relationship is highly charged with personal meaning, emotional investment, and subjective perceptions. It is open to inquiries and debates, which have enormous consequences for the people in the relationship.

These observations clarify how a relationship comes to be through communication. The more people communicate with each other, the longer the relational event lasts and the more complex it becomes. The history of that relationship will always be the narrative of how the parties communicated and how they felt.

Here is a more formal way to say the same thing.

The being of a relationship is constituted by the interaction of two or more entities. The communication could be physical, visual, verbal, or, most likely, some combination of all these. The entities need not be conscious or physical. (I have a kind of relationship with the chair I’m sitting in right now.) The communication may be poor—in fact, it usually is. The interaction may be brief, lengthy, or intermittent. The communication may cease. Regardless of these variables, a relationship is always a history of communication. That event, once it occurs, is an objective reality—a reality that is often confused with subjective perceptions.

This general account of relationships helps explain our relationship with God.

How can God be absolutely independent of us and still have a relationship with us? Because all beings are independent of each other, even when they are in a relationship.

What constitutes our relationship with God if he does not need us? The same ground that constitutes all relationships: communication. God has spoken to us many times and in various ways.

How can we respond to God emotionally if we don’t understand his inner life? We can respond to him emotionally in the same way we respond to human beings we don’t understand. God communicates with us. We communicate back. The communication is loaded with subjective significance for us. Sometimes God says things that give immediate encouragement. Other times we misunderstand his messages and have to struggle with them.

But how can we become intimate with God if all we have is this objective communication event? We become intimate with God the same way we become intimate with human beings: communicate more. Reflect on the communication in the past. Clarify it. Relate it to recent communication. Intimacy is just deeper and deeper self-disclosure. God’s self-disclosure takes the form of Scripture and the indwelling of his Spirit. We listen to him through study, prayer, and meditation. Our self-disclosure to him takes the form of prayer, confession, and praise, through which we say what he means to us.

The accusation against classical theism is that God’s aseity makes a relationship with him impossible for human beings. If my account of relationships is true, then the accusation fails.

Our illustrator, Paul Mathers, posts a drawing almost every day! Check out his Instagram here.